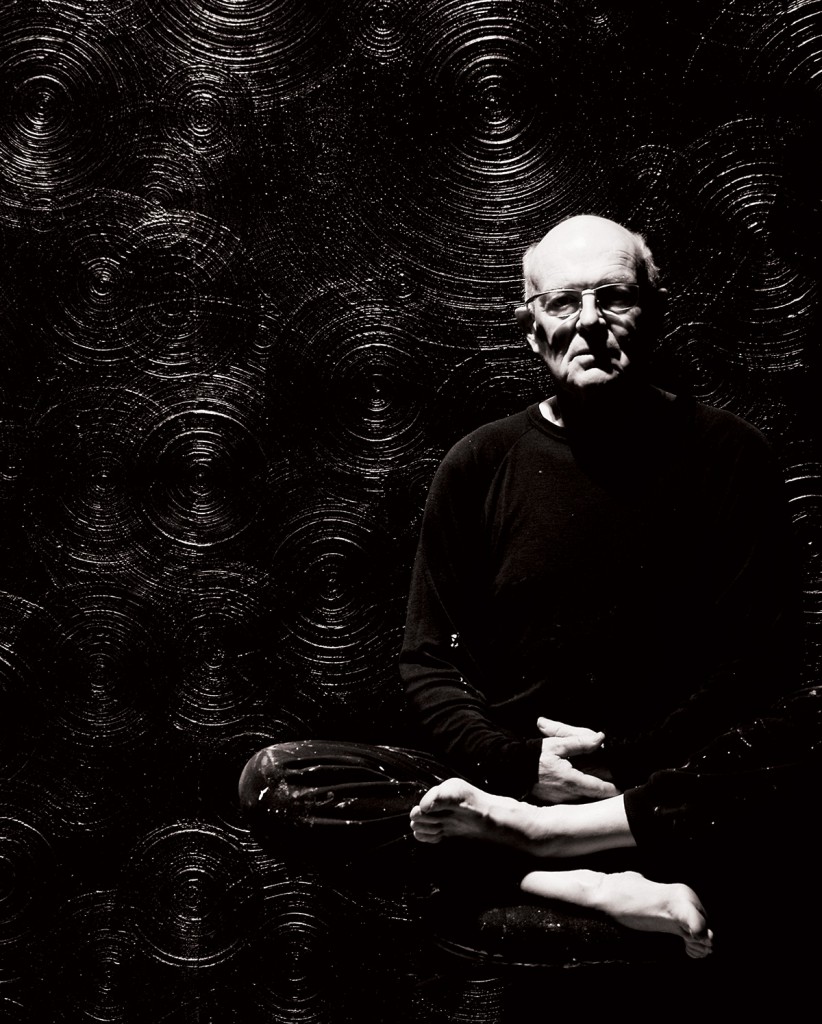

To walk inside the home of artist Asher Bilu and his wife, Luba, is the stuff of considerable wonder. Known for large works of abstraction, Asher’s authentic Victorian Brighton abode acts as an informal survey of his creations, ranging right through from his very first painting in 1958, which hangs on the wall of the front study.

It’s hard to know which way to turn when entering the Bilu home. An Alice in Wonderland chequerboard floor spreads out before you, while overhead, paint chandeliers reach out like multicoloured jellyfish tentacles. Accustomed to the space — or lack thereof — Luba points out curios here and there, like a magnificent oversized necklace (now framed) by an artist named Horse that she claims she only wore once to the official opening of the Victorian Arts Centre. And then there’s the engrossing golden display, like a solar system of planets and stars, hanging from the ceiling of their lounge room. It’s hard to believe this beautiful survey of the constellations serves as a secret, permanent and dazzling fixture suspended overhead, that is one of the central features of the artist’s home.

Even the kitchen has fallen victim to encroaching artwork. Decorating the walls and surfaces are tiny Japanese tiles, which Asher collected and then constructed into sheets like wallpaper (holes for power points, etc, accommodated) so they could be attached to the walls swiftly as a surprise for Luba when she went to work one day. ‘Luckily, I liked it,’ says Luba of the colourful display that greeted her on her return.

Emerging from an aural cocoon of traditional Indian music, Asher ventures inside from the two immense studio workspaces he’s established alongside the house.

‘We add, we don’t change,’ says Asher, now ready for his 11am coffee and cookie break, of their interior designing approach. ‘There’s never been a case when I thought, “I can’t live with that, get rid of it.” ’

Luba indicates a silver tray that’s filling a space low on the wall. ‘There was nothing there before but, once it goes there, to take it away it looks empty. You can always find another space on some wall. Somewhere.’

As if looking for that elusive spare spot, Asher peers under a sideboard where an old rice sieve hangs. He jokes, ‘It’s a beautiful thing from China… It comes from a very interesting part of China called “Bendigo”.’

Luba clarifies Asher’s humour: ‘We bought it in Bendigo. We thought it would make a great fly cover for the food at barbecues.’

After a chuckle, the conversation turns to more serious matters. How do the artistic processes unfold for Asher?

‘I don’t work nine to five,’ he says. ‘It depends on what I’m doing. Basically, when I work, I’m full on. I just work from morning to night, have a break then either go back to work or play my music. It’s not a compulsive thing. It’s just where it takes you. I just do what needs to be done.

‘Sometimes it’s more inspiring than other times. Right now, I’m working on a big thing so it’s wonderful to get up in the morning. The beginning is always interesting — the burgeoning of an idea. It’s like falling in love: it’s difficult in the beginning, then there’s a fun part and sometimes there are mistakes. I’ve divorced a few paintings.

‘It doesn’t happen often but you’ve got to acknowledge the fact there can be failures. I’m not compulsive but I’m possessed when I’m working.

‘My favourite story about work processes comes from an interview given by an American painter called Larry Rivers — a pop artist,’ he recalls. ‘They asked him to describe a day in his working life and he said, “Well, I get up in the morning, eat breakfast with my family, read the papers, and then I catch the train or the bus or whatever and go to my studio, then I open the door, hop into bed and go to sleep.” This is wonderful because a lot of people think you arrive at your studio and then you just start. No, let’s go to sleep… let’s have a dream.

‘I think the artistic process on the whole is absolutely fascinating. I wouldn’t change it for anything. The feeling of creating — giving birth to something new — is really very rewarding in every way. You’re contributing something, you’re creating something, you’re living something… and when it works, it’s fantastic. It’s one of the most exciting things about being an artist.’

For Asher, his domestic space is the core of his inspiration. ‘Once I visited a house in Los Angeles designed by Frank Lloyd Wright. The people who lived there were the original people who had commissioned the house. They were old at the time, and the house looked like they had lived in there for many years. It had all the signs of the times — Picasso drawings on the walls, sculptures… everything looked worn out and lived in…’

Luba offers a word: ‘patina’d’.

‘The people and the house had evolved together,’ Asher continues. ‘It was wonderful. That sort of age… like a good wine… what time does… You can’t create this (he gestures around the house) in a hurry.’

‘There’s a culture of replacing today,’ remarks Luba. ‘Nothing is made to last. Something wears and you immediately replace it with something new.’

Asher continues: ‘Time is fascinating, what it does. In art direction, you try to create this sort of thing, which you can do up to a point. Everywhere I look here (in this house), there are things from one of our journeys… and memories…’

He grabs a lump of whitish stone from the side table. ‘This was from Death Valley. We picked this up because we thought it looked like a car but it comes from Death Valley. This stone was lying for thousands of millions of years baking in the sun… and now it’s living in Brighton. How would you know that this rock would end up in Brighton?’

Asher tips a jar of various stones and rocks on the table and his excitement noticeably rises. ‘These are Aboriginal flints,’ he says. ‘They’ve been carved. This is the head of a spear. This is thousands of years old. Look at this beautiful piece of carving. To do that, you really have to be skilled. The spear itself was about four metres long.’

Try coercing Asher into naming a favourite part of his house and he draws a blank. Luba doesn’t hesitate to pinpoint her bed… with the electric blanket. But seriously…

‘This house is a rather unusual house on the main street… and the gates, everyone recognises them,’ explains Luba. ‘A couple of weeks ago, I got a phone call saying, “Have you lost your mobile phone?” My mother who lives with us, she’d dropped it. And we all know that everyone has ‘home’ on their phone, so they rang it, and home was here. A guy came to drop it off and he said, “Oh, I’ve always wondered who lived here and what it’s like behind that fence.” The locals feel that way about our place. They can see the things that stick up over the fence and the decorated gates…’

Asher cuts in: ‘One time, we went out and there was a wedding party outside our gates taking photographs. Apparently, the photographer has been bringing brides here all the time. He should give us a commission for the first night or something.’

For Asher and Luba, travel to far-flung places is an integral factor of their life together. Asher’s interest and formidable skills in playing the Indian instrument known as ‘sarod’ have made India a repeat destination for the Bilus.

‘Travel is another form of work. I work all the time… my eyes, my mind,’ says Asher. ‘I don’t take photographs or do drawings. I absorb. It all goes into the computer (he taps his head) and whatever comes out after it’s been processed… fine. That’s it.

‘I’m working now on a series of paintings. This idea I’ve had for years, but somehow, it was lingering in my mind and I thought, “I’ll do it some day.” And then, all of a sudden, without planning or anything like that, it just went “bang” in a big way and I did it.

‘You store these kinds of things and they come out and it’s wonderful. I’ve thought before that I should write down an idea, but then I think, “No, if it’s going to be good it’s going to stick and, if I’m going to forget it, let it go.” Occasionally, wonderful thoughts just go away. I really should write them down but…’

Given the plethora of artistic creation that fills Asher’s physical reality, we can only assume some of those ideas he’s failed to write down have managed to stick and, consequently, germinate. In terms of finding space to hang new pieces in this home-based ‘gallery’… well, that’s another issue.

‘You’re looking at 33 years here… This is what happens and it doesn’t happen overnight,’ admits Asher, somewhat in awe himself.

Despite his talent for producing individual pieces, one look around the home he’s built with Luba — and the many photos of the Bilu family lining shelves, bookcases and battling for attention on the walls — and it’s clear this sum of parts is his greatest creation of all.

Comments are closed.