Melbourne artist Ivan Durrant, who reminisces about the wild child SoHo heyday of the great Super Realist art movement.

It was the end of 1975 and the leading American Super Realists, Chuck Close and Janet Fish, had just exhibited at Tolarno Galleries in St Kilda with my then dealer Georges Mora. Georges had already sold one of my Super Realist (photorealist) paintings through a leading gallery in New York. I said to my wife: ‘Let’s just get over there and mix it.’

In September 1976, with Judy and my two children, Jamie 4 and Jacqui 6, I spent the first night at the so-called famous Chelsea Hotel. Yes, there was a huge Brett Whitely in the foyer and the Rolling stones had stayed there, as did anyone hip and famous at the time. But one night was enough: what a sleazy dump. The corridors were lined with people out to it on heroin, our room had saucers with rat bait in the corner, and some drug-crazed maniac screamed and banged at our locked door all night threatening to kill us. We got out at six in the morning and headed downtown to Soho.

Luckily for us, Australian painter Bob Jacks, the resident frontman at the famous Broome Street Bar, had secured us a gigantic, ex-factory-floor loft in SoHo. It was about a five-kilometre walk carrying two suitcases, dodging doggie doodoo, with two bewildered children in hand. We were stopped at least twenty times by locals staring at my wife and children and wanting to touch their hair. Everybody in New York had black hair, so with red hair they could have been from outer space. But to me it was this land, this New York, that was completely alien.

The cityscape was so foreign. I couldn’t believe how dull, how grey, the sky and light was, even on a day the home crowd considered full of brilliant sunlight. The place was devoid of nature: tall buildings, dark shadowy windswept streets full of litter and cast-offs, steam pouring out of dirty roadways and shopfronts with advertising and neon all over them. It was almost impossible to cross a road without being skittled by a yellow-dinted taxi or flashy chrome-polished Pontiac, Buick or Cadillac. The only open spaces were a carpark or a cyclone-fenced, bitumen’d, graffiti-covered basketball court. But the noise dominated: the continual bipping of horns and those non-stop sirens – police, ambulance and fire trucks – blasting all day and night. I’d often wake in the middle of the night thinking the whole city was on fire.

Settling in to SoHo was a breeze as Janet Fish, who had stayed with us in Melbourne, arranged a dinner party at her loft to welcome us. Guests included Chuck Close who lived above her, a couple of writers and a puppeteer who performed for our kids. One puppet was a ventriloquist doll with its own ventriloquist doll sitting on its lap – what a great concept.

SoHo was the centre of the universe for art in the Seventies, and what a great place it was. Seeing Debbie Harry or John and Yoko walking the streets was quite normal. Every street block had an art gallery on every corner; even going to four openings a night, seven nights a week, which we did for six months, we still couldn’t see it all. It wasn’t unusual to finish up at a party at some random artist’s studio at least two nights a week. It was at one such soirée that Warhol swapped me a pair of his sunglasses for a pair of R.M.Williams boots. I was never quite sure whether the Warhol gathering was a party, a celebration, or if we were just part of an art happening he was filming.

The first galleries we visited were Louis Meisel Gallery in Prince Street and OK Harris in West Broadway, both jam-packed full of Super Realist paintings. They were all there: Robert Cottingham, Don Eddy, Ralph Goings, Richard McLean, and at least 10 others, except for Janet Fish and Chuck Close, who exhibited uptown. It was like walking into the Sistine Chapel the day after Michelangelo finished painting his ceiling. I was totally knocked out; instantly, I understood the enormity of Super Realism. I’d walked through their city for a few days now, but not being a New Yorker I saw the world through fresh virgin eyes, the eyes they were offering the viewers – the joy of observation. There was a detachment, a non-involvement with the melancholy or morality of the subject; the paintings were a clear statement of seeing the real world for what it was and what it had become, without preaching. They had found a new way to the truth; painters before had attempted in some way or other to achieve realism, but with judgement and nuance. Art had lost, or maybe never had a way to see the real world.

Up to this time art had culminated in Pop Art, Abstract Expressionism, Colour Field and Hard-edge Abstraction. Art had become its own subject, and a highly valued and traded commodity. America and Australia were in a deep mess over the Vietnam War and the public was becoming restless over the censored information and news footage they were being fed. It became glaringly obvious there was a need for truth when leaked photographs and film footage revealed the real horror of war: a look at where our greed, exploitation and modern consumerism had led us. Someone had to freeze the world in its tracks and take a good hard look. That’s what the Super Realists did.

The insistence on photographs as a source material guaranteed that the artists accepted what was in front of them as something worth looking at. Yes, they were banal in a sense – street scenes, shopfronts, neon signs, cars and bumper bars – but there’s no doubt there was something new and questioning about the focus on the objects around us at a particular moment in time.

Look at Richard Estes’s work: his glass shopfronts bombarded us with so many reflections, and distortions of reflections on those reflections, that the shops almost became ghosts of other shops. It takes a lot of concentration and changing of focus to see this truthful situation if you’re standing in front of a shop. You’re inclined to just look at the goods in the window. But how amazing, how telling of the world around us is Estes’ window? He makes no attempt to glorify or condemn the world in his window, but to me, the result gives a new optimism as it opens up the real world around us.

For all the great art in New York, it was the Museum of Natural History on West Broadway that had the greatest influence on me. Feasting on amazement and awe, I visited and photographed diorama after diorama for at least six weeks – talk about Super Realism! The backdrops and sculpted foregrounds were so convincing, their stuffed animals placed so eerily in such a natural way, that it was hard to convince myself I wasn’t on the spot, in some jungle or African plain. I’m telling you, the illusion was staggering. Somehow these animal-filled environments behind shop-like glass windows fitted so well with the current art movement.

Back in Melbourne in 1977 I built my own diorama, a butcher’s shop. Quality Meats is a free-standing shop where the sculpted meat in the window looks so life-like, or should I say, death-like, that even I’m convinced it’s the real thing. It’s not a patch on the vastness of a real butcher’s shop; nevertheless its honesty in realism compels the viewer to contemplate, and whatever they contemplate is up to them.

Super Realism didn’t just have its distrusters, it was openly condemned for years as scorn raged on its painters for daring to copy photographs and call it art. It was an affront to all the art learning, criticism and practice that had preceded it. We all know and understand how hideous the condemning of Impressionism, back in its heyday, appears today. When Matisse painted The Joy of Life in 1906 it was a leading Impressionist and member of the Avant-garde, Paul Signac, who himself complained the loudest. Signac said Matisse had ‘gone to the dogs’. He called Matisse’s use of colour disgusting and said it was ‘reminiscent of shopfronts of the merchants of paints, varnishes and household goods’. Yet when Picasso painted Les demoiselles d’Avignon, it was Matisse, in turn, who was outraged, claiming that Picasso had painted it to ridicule the Modern Movement. It’s now 40-plus years since the beginning of Super Realism and the world is finally catching up to its significance as an art movement.

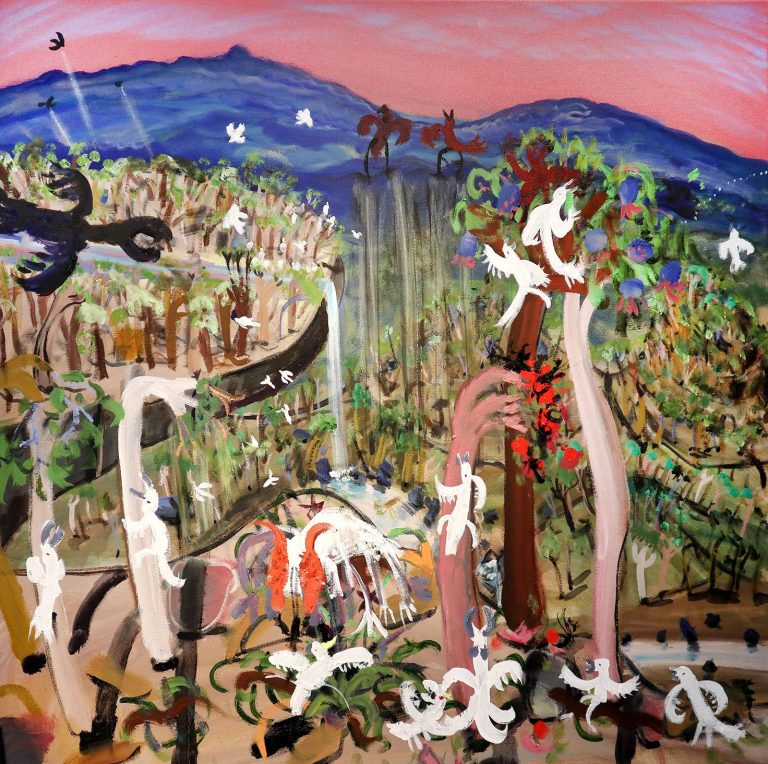

Article Hero image:

Comments are closed.