Australian artist John Peter Russell was an adventurer, a generously spirited, warm and charismatic raconteur. Little wonder that Robert Louis Stevenson, inspired and intoxicated by Russell’s colourful tales of teenage years, spent voyaging to faraway exotic islands full of overly welcoming native girls and an abundant, never-ending supply of tropical fruits and fish, where any dive in the ocean could bring up a bucket of pearls, headed off for the South Seas. For the ailing, mentally exhausted writer, a new home and lease on life was offered.

But it was Russell who found the true treasure island – Belle Île, off the west coast of France. Satisfying his search for fulfilment, he discovered an overflowing chest of brilliant pigments: love, family, and creative companionship in the continual flow of visiting artists. His great friend Van Gogh had struggled to achieve his dream of an art colony in Arles, failing miserably at his first and only attempt through irreconcilably violent conflict with Gauguin in the Yellow House. On the other hand, such a colony grew organically on Belle Île as a reflection of the Australian’s sympathetic and empathetic approach to all with whom he came in contact. Gauguin was the only exception. His disgraceful, syphilis-spreading attitude towards women was never to be countenanced.

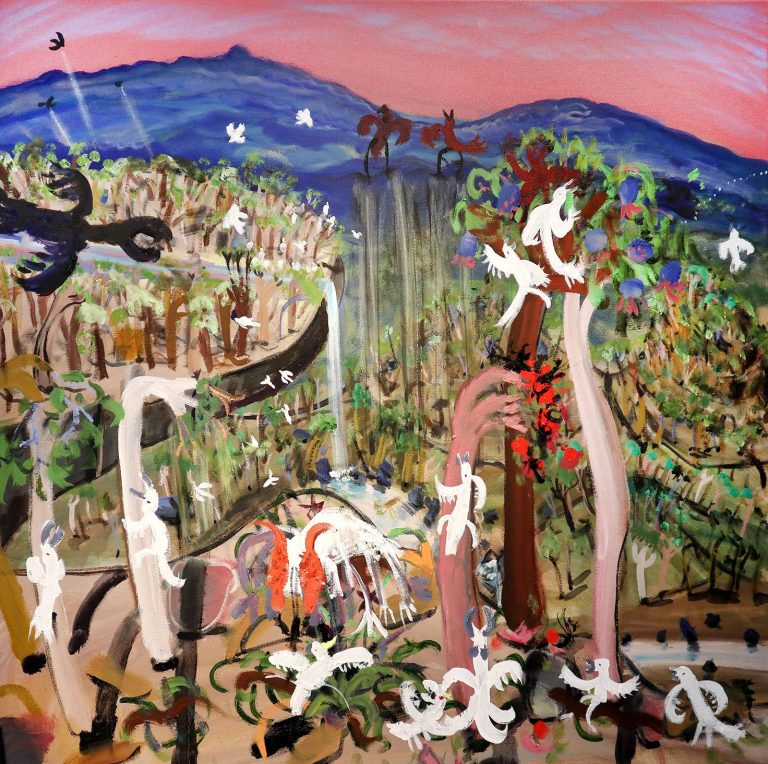

More Fauve than Impressionist, Fishing Boats, Goulphar, 1900, a view of Belle Île from the sea, shows Russell at his creative peak. Searching for honesty and humanity, he lays open his entire life for all to see: it’s a painted autobiography.

As Russell viewed the sea, he noticed the fishing boats’ red sails had a strong visual impact with their powerful, brilliant, raw scarlet reflections. During his teenage voyages, Russell made his first tentative attempts at drawing and painting, mentally committing to art as his future. The sunsets and sunrises, doubled in power by their uninterrupted reflections, reminiscent of an Australian bushfire, must have made an indelible imprint on the emerging artist. With his never-dying love for boats, boat-building, and the sea, Fishing Boats, Goulphar shows how deep into his soul he reaches to paint.

Finding the perfect colours to express how he felt about nature was a dominating obsession with Russell, as repeated many times in the letters he wrote to his old travelling mate, Tom Roberts, back in Australia. Russell had painted side by side with Monet on Belle Île, mastering the Impressionist technique so expertly that Monet was compelled in a letter to a companion to say: ‘That friendly Australian chap’s paintings are better than mine. ‘

But Impressionism wasn’t enough. Likewise, the scientific approach of Seurat and Pissaro, with its colour spectrum theories of dots and dashes, left him cold. He needed something more direct, more brilliant to tell his story. The only way out was to grind his own pigments in an inner search for accurate colour and a new approach. How perfectly he tells it in paint, on the cliffs at Belle Île: echoing that gold and green pure light dancing and flickering through the rich wet tropical leaves. The bright red and orange tropical flowers that he’d discovered when sailing through the Coral Sea to the Orient – such a harmonious backdrop to the sunset sails.

Then unexpectedly, right through the centre of the cliffs, he places a deep, dark gorge leading down to the water, menacing with its sense of evil and foreboding. The heavy blues and greens express tension against the contrasting landscape and sea. It’s a warning: ‘Attempt to leave your island home and friends, head back to sea… you may be heading to your death.’ All that Russell desired was anchored at the top of that cliff: his home, wife Marianne, nine children and his extended family of creative friends. He’d been denied family as a boy when his dominating father sent him from Sydney to boarding school at Goulburn, 200 kilometres from home. Later, as a teenager, sent to sea on a shipboard apprenticeship. He knew loneliness but had the personality to overcome it, making friends wherever he went, no more so than in the art world where many leading British, French, American and Australian artists spent time at Belle Île. Some came to learn how to paint under his guidance, like Matisse, and others sought comfort, like Rodin during his most depressing period, when the establishment had shunned his sculpture of Balzac. Russell praised it and immediately commissioned a bust of Marianne.

Fishing Boats, Goulphar, marks a turning point in art history and cements Russell as a creative and leading innovator. As he said to Matisse: ‘A new way of painting will evolve on the shoulders of Impressionism.’ Russell found it using broad areas of colour in a poetic expression of mood. And it was only five years later, in 1905, that Matisse headed the exhibition that first gave the Fauves their name – the so-called ‘Wild beasts’, for their use of broad raw colour areas to achieve the same end as Russell.

Unfortunately for John Peter Russell, his insistence on not competing with his fellow artists through exhibitions led to his outstanding achievements being partly undiscovered and sadly undervalued. He should be placed at the top of the art tree with his great friends Monet, Van Gogh, Matisse and Rodin.

John Peter Russell

Fishing boats, Goulphar

Comments are closed.