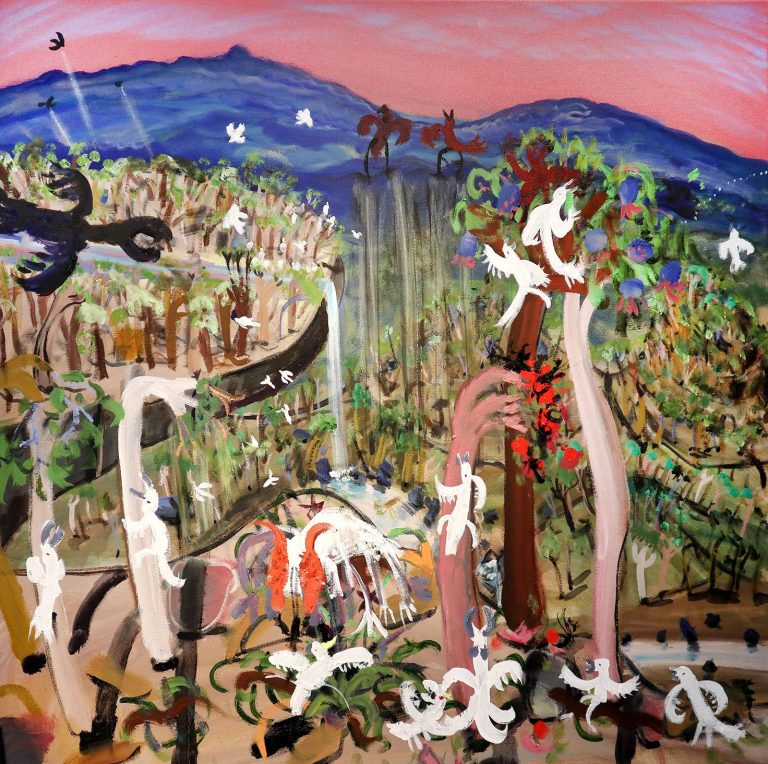

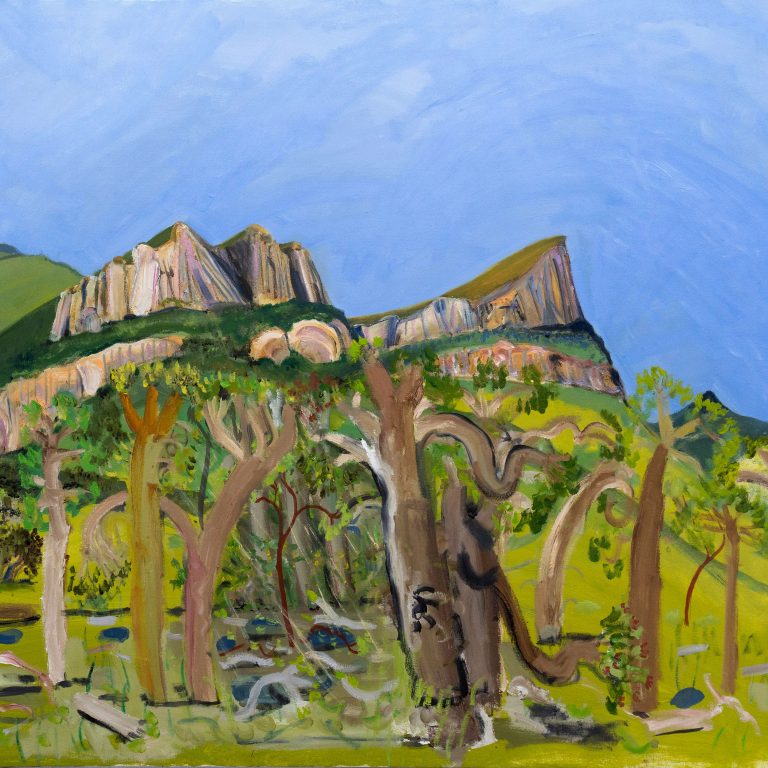

Arriving in 1951 from Paris, Mirka and Georges Mora transformed the Melbourne food and art scene. Their cafés and restaurants offered sophisticated food and their Tolarno art gallery inspired and energised the rich and famous. Launched in the year of Mirka’s 90th birthday and her passing, Mirka & Georges: A Culinary Affair, a new book release from MUP, gloriously illustrates the Mora’s extraordinary story. Recalling his first exhibition held at Tolarno in 1970 and the energy of the time, artist Ivan Durrant also celebrates the memory of Mirka and Georges.

Mirka & Georges: A Culinary AffairMirka & Georges written by Lesley Harding and Kendrah Morgan, senior curators at Heide Museum of Modern Art, is available in all good book stores now.

Mirka & Georges: A Culinary AffairMirka & Georges written by Lesley Harding and Kendrah Morgan, senior curators at Heide Museum of Modern Art, is available in all good book stores now.

Comments are closed.