It’s easy to be reminded, how great an artist Charles Blackman was, especially with his painting Girl with a Nosegay (pictured). You have to stop – it’s a mesmerising magnet. You’re into his poetry, life, mood and love, boots and all. As Charles said to me on our first meeting in 1969, you can’t make art without love. To paint is to make love to the world.

In the early 1950s Blackman was a cook at Georges Mora’s famous Café Balzac restaurant in Melbourne. Anyone who was anyone in the creative world here or overseas ate there. In the late ’60s Georges shifted to St Kilda where he started Tolarno Restaurant, and Tolarno Galleries in a back room. Georges became my art dealer in 1969. Almost every night after the restaurant closed I sat drinking red wine with him as he told me all sorts of stories about him and Charles. The one that bothered Georges most was how he would sit sharing wine with Charles every night after closing time at the Balzac while Charles sketched on butchers’ paper, at least one hundred drawings a time, throwing them in the bin as they left. Such torment for an art dealer; millions and millions down the drain.

When I joined his gallery as a young artist, Georges gifted me an old easel on which, he said, Charles had painted all his schoolgirl series of paintings. How lucky was I at the age of 22 to dine with Charles and his wife, Barbara, and Georges and Mirka at Tolarno every time the Blackmans visited Melbourne. At least twice a year Georges would insist on taking me to Sydney to visit Charles and eat at his favorite restaurant, Eliza’s at Double Bay, Sydney. I always ate Eliza’s prawns; Charles always had lobster, and good old Georges always footed the bill.

So I got to know Charles really well: a petite, bright-eyed, quick-witted bloke he was, always quoting lines from poetry and fitting clichés with his own twist into the conversation. Come to think of it, my fellow painter and mate Asher Bilu has the same style of repartee. But our conversations about commitment to painting, reaching inside your soul and letting it out on canvas, giving it to somebody else as a gift of love, were what moved me then and drive me now.

His painting Girl with a Nosegay is Blackman at his strongest: so deep and moving, so passionate and caring, yet it’s not possible to put a finger on its exact meaning. This is truly where art performs a function that words can’t, which in my mind is what it’s all about.

To me, the girl is excessively shy and too intimidated to face the sunlight of the world. Her only sustenance is the light reflected on her face from the posy she is holding. But I have to ponder: is she receiving the flowers, or giving them as a gift to us the onlooker?

Whatever the case, it’s clear there’s a need for love (the gift) to sustain her and us – the main subject of all Blackman’s work.

There’s a sense that she is so vulnerable to the world around her that without the gift of giving or receiving she may be pushed back into the dark abyss of a life with fear. She can only survive with the love of others and love in her heart. This is a perfect example of Charles’s natural and uncanny ability to move all who view his work.

The background to The girl with a Nosegay is startling and seemingly incongruous in style compared with the main subject. Here, Blackman applies the paint almost as if he had used a jagged scraper for applying tile glue to a bathroom wall; the colour reminiscent of 1950s Laminex or wallpaper that might have been found in a modern Australian home littered with teak and Fler furniture. He deliberately shows the girl holding the posy – an allegory for love in his own mind – as a cut-out, transposed into the real world. So there’s no way this girl, this message, can be written off as a poetic fantasy: love is the sustaining force right now.

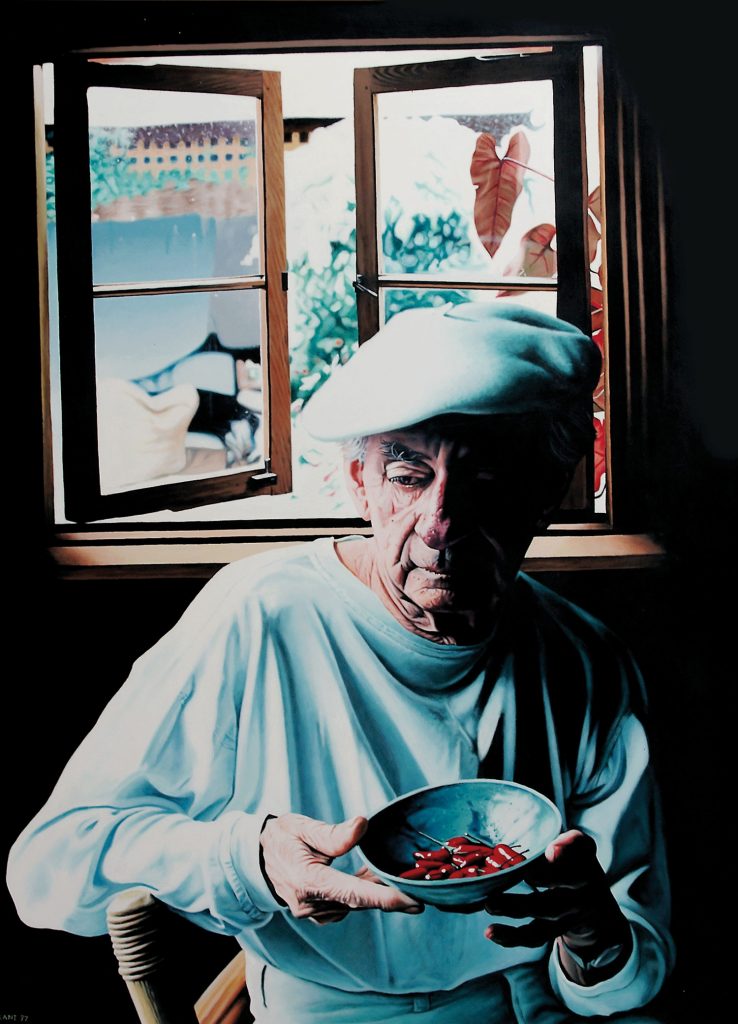

In 1997 I visited Charles in Sydney to paint his portrait for the Archibald. I wanted it to be a homage to him and his work. Unfortunately it didn’t make the cut and was not shown. Charles was very frail at that stage, struggling a little with memory loss and ill health, but it took only a couple of minutes talking about the ’70s for him to spark up, back to the almost cheeky, wicked-child state that he had lived in all of his life: a man with true freedom of mind. We went out to Doyles for a fish lunch, then I took him to a large Blackman exhibition at Denis Savill’s gallery. Charles didn’t even know it was on at the time, and looked a little bewildered when we walked in. How he bucked up when a beautiful woman recognised him: quick as a flash he pulled a flower from the vase on the desk and handed it to her. We had a great day. I did a few sketches and took a few snaps and went back to Benalla to work. So there it is: I painted him in his world, a world of dark shadows, limited palette, and a garden somewhere. The most important thing was to convey what a thinking man he is, and how he could drift into a fantasy space of his own to gather gems to paint. The mood I was searching for is summed up in his right eye; that is, the left eye as we view the painting. It took me two weeks to do the whole painting except for that eye, which took another two weeks to get right – to get that sense of drifting back and dreaming, to get that old Blackman magic into the work.

When he was sitting for me I explained to Charles the feeling I was after, that I wanted to put him in the world of his paintings – and asked if he thought it would be a good idea to hold a posy. He quickly grabbed a bowl of chillies from his window and said: ‘These are my flowers: so beautiful, but get too close and they’ll burn you.’

I took the completed portrait back to show him. ‘What do you think I should call it Charley?’ Lightning-quick he came back with a typical Blackman twist: ‘Life is a bowl of chillies.’ So that’s the title.

Is it any wonder his work knocks me out? Here’s to you, old friend – Ivan Durrant.

Comments are closed.