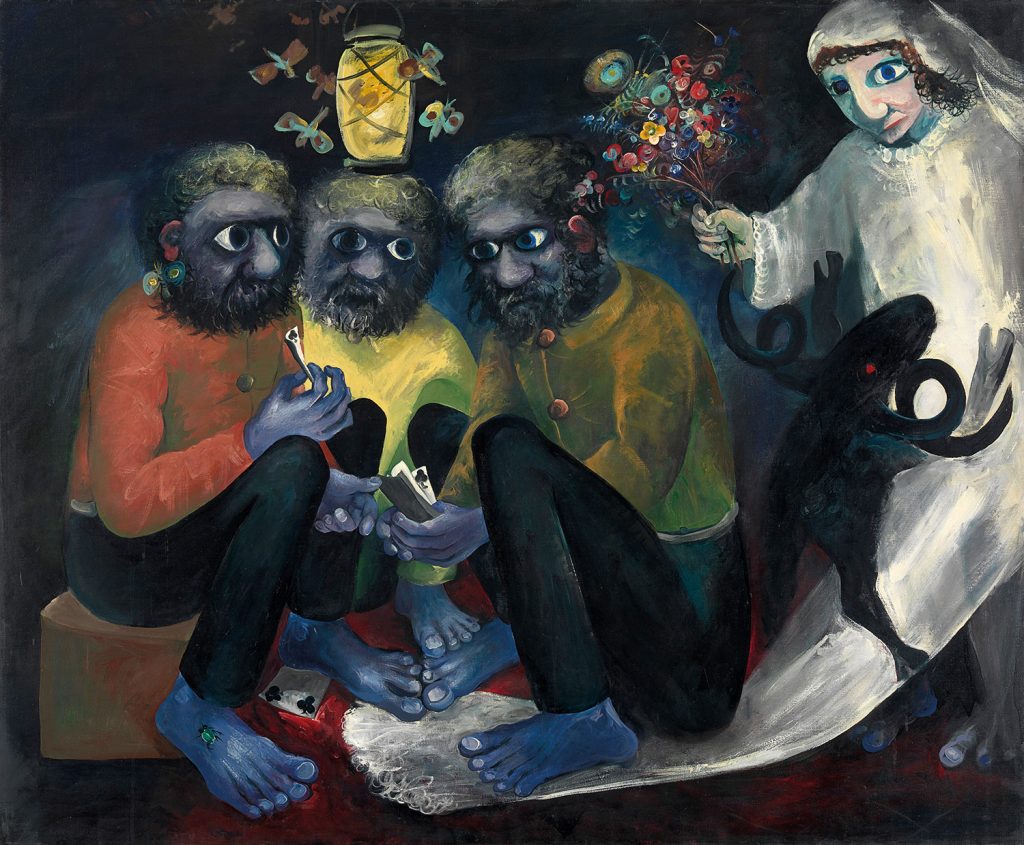

The 1957 Arthur Boyd painting Shearers Playing for a Bride is the most powerful and emotionally moving work I’ve ever seen – it’s haunted me for over 40 years. It is one of the 30 paintings of his Love, Marriage and Death of a Half-caste series, commonly known as the ‘Bride series’. It’s a deeply personal response to the dispossessed, detribalised Aboriginal peoples – victims of the ill-fated assimilation program of 1930 – that he encountered in 1951 on a 4WD trip from Alice Springs through the Simpson Desert. Denied their culture, they lived in a wretched state, in some kind of never-ending nowhere land with seemingly no meaningful future prospects. Arthur was shocked and totally devastated by the treatment of what were known then as ‘half-castes’, living an evermore shunned, confused existence. These paintings were revolutionary, outspoken, so needed for the times – and even more relevant today: great art can do its work for decades. We’re invited deeply into the artist’s psyche, full of symbolism, allegories and internal emotional tortures. Boyd is a man never afraid to put himself on the line.

Just look at the yellow-glowing invader’s lamp hovering above the card-players’ heads. Imposed on nature, mesmerised moths dance around it, unaware of the danger in this new world, doomed. Death is the inevitable outcome when they are finally incinerated. This artificial light burns without a scrap of feeling for place and what damage its interference is causing.

The three indigenous card players – barefoot, fancy-dressed against their will in colonial soldiers’ uniforms – like the moths, also hover around the same yellow lamp glow, pathetically gambling. It’s a sad scene of imposed destruction. They’re forced away from their culture as all semblance of their world disappears and they’re left with despair and the worst habits of European settlement. Their jackets are unpressed and no doubt old hand-me-downs, used by their invaders as an ignorant symbol of assimilation. But Arthur paints them without shoes. In better times, bare feet were once a proud way to travel, but here echo the despair of Depression families: harking all the way back to the orphans and street urchins of Charles Dickens. We are left in no doubt as to how Arthur feels; as a viewer, I feel it too.

Like all brides in this series, she appears white, but her black bare legs and feet create an ambiguity – she’s possibly a ‘half-caste’, but maybe also a representation of the unworkably split cultural environment she and the shearers are forced to live in. Her white lacy fairytale/princess wedding dress jars as incongruous and over-dressed for their world. On the one hand, her dress portrays her sincerity and the belief she holds in her black groom, yet she’s a ‘half-caste’ chattel, the prize in a card game. She offers up a posy off flowers but the flowers are not of the Australian bush. They’re from an English cottage garden, full of colour and hope yet doomed to wither and die. She is is anchored down by her veil, for one of the card-players – possibly her groom to be – sits on it. For her there’s no escape: she’s born into, or has joined, the ‘unwanteds’. Her bare feet symbolise to me her decay into wretched poorness – yet another vision of her future. The world these card players inhabit is, in a way, itself half-caste: unforgiving, unreconcilable, it is dominated by its new invading masters. They’re victims of ignorance and greed.

Possibly the most confusing and grotesque shock comes from the red-eyed black curly-horned devil ram clinging to the bride’s dress. Arthur quite often painted copulating beasts looking at lovers, or bestiality itself, heavily influenced no doubt by his childhood religious upbringing. He struggled to reconcile love and lust, the latter being a biblical no-no. He had his own demons, being a married man but taking a lover. In this case the evil of lust doesn’t reflect on the bride and groom; it creates, instead, an overwhelming sense of deep wrongness to the world built around them. Like many of Arthur Boyd’s symbols, the beast and the bride are not to be taken literally. It’s an image to be taken on trust and absorbed for the unsettling value it adds to the emotion in the painting.

Fortunately attitudes have changed in more recent times, and the concept of a ‘half-caste’ is not only irrelevant, but repugnant. If people have indigenous heritage, they simply are who they are. For Arthur Boyd, his perception of the ‘half-caste’ was the outcome of exploitative white behaviour where the child was denied existence by the father and left to fate. The Bride series marked Arthur Boyd as one of the most empathetic and poetic painters of all time. He is my benchmark.

Image caption: Arthur Boyd, Shearers playing for a bride, 1957Oil and tempera on canvas, 150.1 x 175.7cm National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne. Gift of Tristan Buesst

1958 © National Gallery of Victoria

On display within Colony: Frontier Wars

Colony: Australia 1770-1861 and

Colony: Frontier Wars

until Sept 2, 2018.

NGV Australia, Federation Square,

Melbourne, Victoria

Tickets and information are available from the NGV website: ngv.melbourne

Comments are closed.