In my early twenties, it was par for the course to make love in the middle of the day on the back lawn, down the beach at night, or while struggling with twisted arms and ankles, fighting off agonising cramp in the front seat of my 1962 Volkswagen Beetle. But never did I expect, at the ripe old age of 64, to ‘do it’ in front of one of the best paintings in the world, on the cold concrete floor in the middle of the Australian National Gallery, Canberra, oblivious to all passers-by.

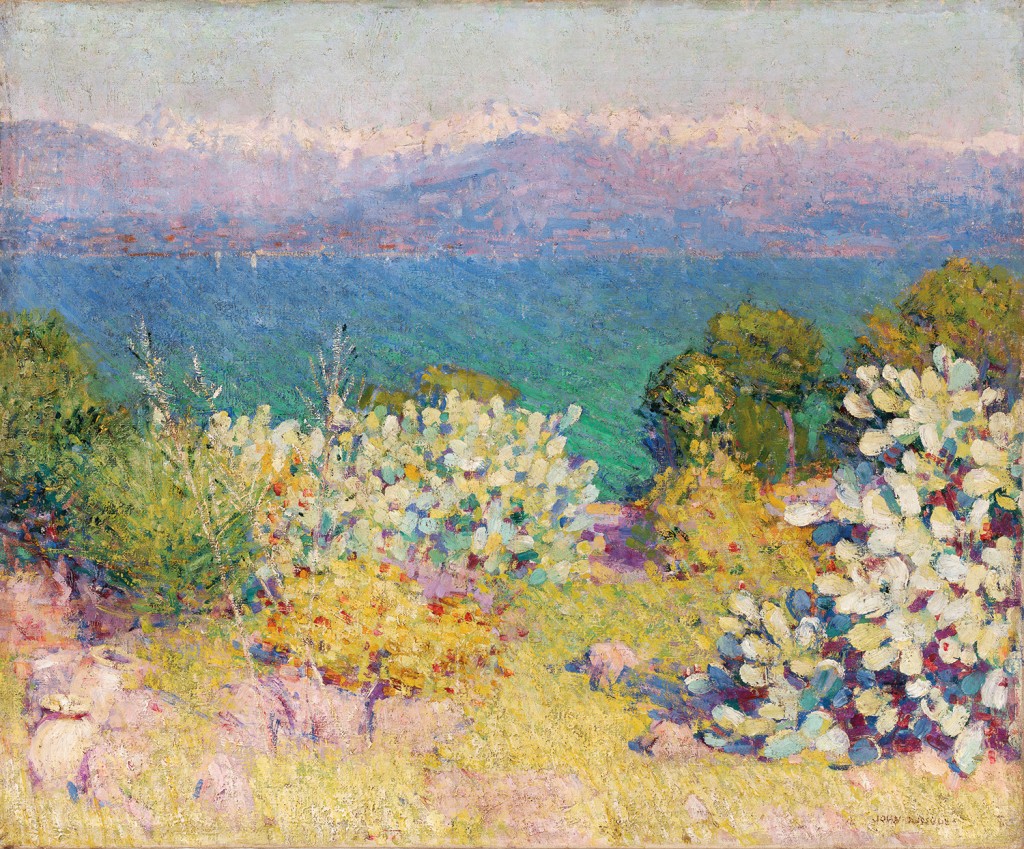

Yes, uncontrollably, that’s exactly what happened. I’d gone to view Monet’s haystack. Next to it hung his greatest masterpiece. Warm, wrap-around, sinking into your body: summer-haze radiated from the miracle Impressionist colours that seemed to be caressed, rather than brushed onto the canvas. There was a passion not seen from him before. This artist knew and loved the landscape and sea. Previously only Van Gogh had displayed such extraordinary emotional commitment, the opening of his heart and mind to the viewer.

The atmosphere in the painting was overwhelming. In a hypnotic sensual trance, I saw myself as the handsome, devil-may-care artist religiously engrossed in the joy of nature, locked in a loving embrace with the woman of my dreams. The concrete floor by pure magic had softened to bright warm summer straw; while the flickering sunlight filtering through the overhanging branches heated and energised us both.

To my surprise, on closer examination, it wasn’t a Monet, but In the Morning, Alpes Maritimes, from Antibes by Australia’s own Impressionist, John Peter Russell. I couldn’t believe it. How could it be, one of our own out-Moneting Monet, with the humanity of Van Gogh thrown in. Here’s a painter that lived and loved in the landscape.

After a little research, I discovered the reason for my confusion over its origins. John Peter Russell, attending painting classes with Van Gogh in Montmartre in 1886, found himself somewhat an outsider from the French clique. He didn’t enjoy the café and night life of absinthe, dancers, and prostitutes, and yearned for the pureness of country and peasant life. After all, he was an adventurer, had already sailed to Tahiti and China, and undertaken endless painting treks through the Australian bush, the French and Spanish countryside.

The haunted and haunting Dutchman Van Gogh, slightly crazed and menacing, quickly attached himself to Russell, as he too didn’t fit into the group, appearing frightening to his fellow students. Vincent was a withdrawn, lonely, somewhat sad creature who yearned for companionship and a confidant with whom he could share conversations about painting. Russell was a handsome, impressively strong six-footer who held the British heavyweight boxing title, and a man of generosity and independent wealth, but in need of reassurance about the quality of his painting. Vincent provided such, none more so than with the overwhelming excitement and pleasure he showed when Russell presented him with the most kindly and sympathetic portrait of the Dutchman dressed as a well-to-do respected artist. Vincent kept it till his death, and it now hangs in the Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam.

Paris life just didn’t suit the Australian and Dutch outsiders, and it wasn’t long before they both headed to the countryside, but in opposite directions, in pursuit of the best they could do.

They were both now equipped with Russell’s belief that true personal meaning could be expressed in plein air painting with colour as the central conduit. Even though personal contact was rare, the two never wavered in their letter writing, discussing art, life, sending descriptions and sketches of their discoveries to each other. There were times when you couldn’t tell their paintings apart. It’s no accident that Russell’s Almond Tree and Blossoms 1887, is strikingly similar to Van Gogh’s Almond Blossoms 1890. They were cemented as brothers of the brush. Nevertheless, Russell just couldn’t understand how Vincent could associate with Gauguin… ‘that disrespecting, careless, syphilis-spreading womaniser with no concept of true love’.

Monet was a leader of the Impressionists with commercial success, and considered a master of colour, when he met Russell. It was at Belle Ile, a tiny island off the west coast of France, where Russell finally settled with the great love of his life, the Italian-born Parisian blonde beauty and model for Rodin, Marianna. Monet decided to venture out from Parisian paintings of parasols for something closer to nature, and happened upon this same rugged coastline that Russell compulsively painted. They had an instant rapport, and Monet spent weeks dining every night at the Russells’, discussing art around the table, and painting with him during the day. He too, got hooked on the same joy Russell had from working in a series – quite often the same outcrop of sharp rocks and grottos around the edge of the island. They even made boat trips together – Russell being an excellent sailor must have been thrilled to give old Monet some new, if not nervous, experiences. Always important to the mix was Marianna, famous for her cuisine. They entertained almost every great artist of the time, including visiting Australians and French masters such as Rodin and Matisse.

Any wonder that first sight of In the Morning, Alpes Maritimes, from Antibes, looked like a Monet? Russell had picked up Monet’s ease of paint application, and Monet absorbed the exhilaration of nature itself, together with an experimental bolder treatment of colour, from Russell.

But in this painting it’s the passion, the love, that I responded to the most. Van Gogh and Russell were equally driven in expressing their life through their work. Van Gogh’s landscapes bombard us with the ferocious anxiety and turmoil that dominated so much of his later life; Russell, on the other hand, a true romantic, had reached the zenith of his life, and expressed the calming pleasure of living with nature and his blissful never-ending love for Marianna. There’s such a poetic serene sensitivity and glow of emotional fulfilment in Russell’s palette.

Great art reveals so much about the artist. I think it’s all about honesty: ‘You are what you paint.’

Image credit:

John Peter Russell, In the morning, Alpes Maritimes from Antibes 1890-91

oil on canvas, 60.3 x 73.2 cm

National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

Purchased 1965

Comments are closed.