I have grown up watching Melbourne Asher Bilu paint. He is a close friend to my father, Ivan. I used to ride my bike over to his house when I was a young boy, and explore his creations, his magical mystery tour of a house, and step deeply into his very private studios watching him carefully touch, construct, paint and, when resting, play his sarod.

I remember well how its unusual sound resonated, and how I felt safe in Asher’s world. I was privileged also to grow up sharing happy moments with a whole kindergarten of children who played in this large house and garden space that so invited exploration.

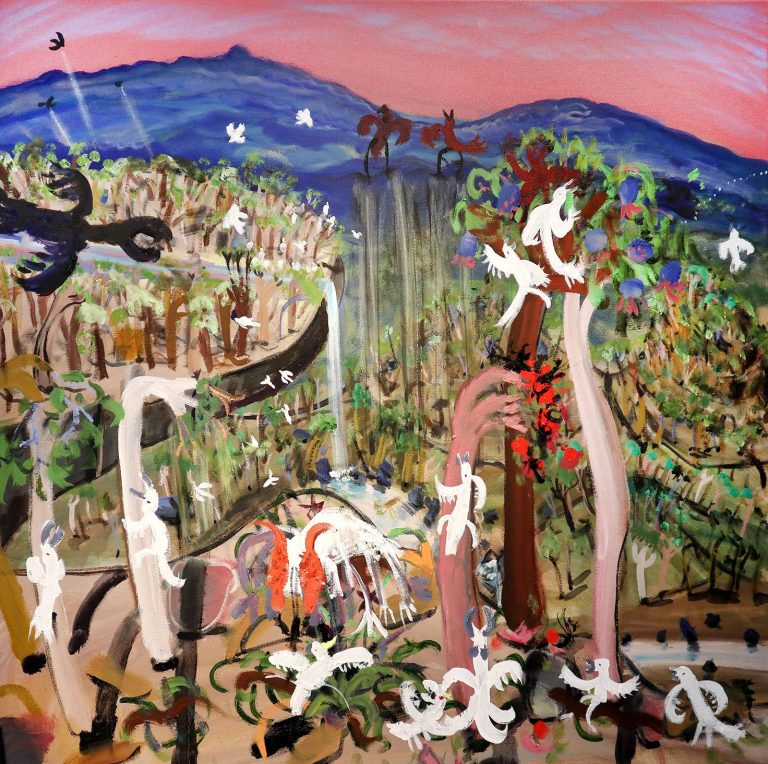

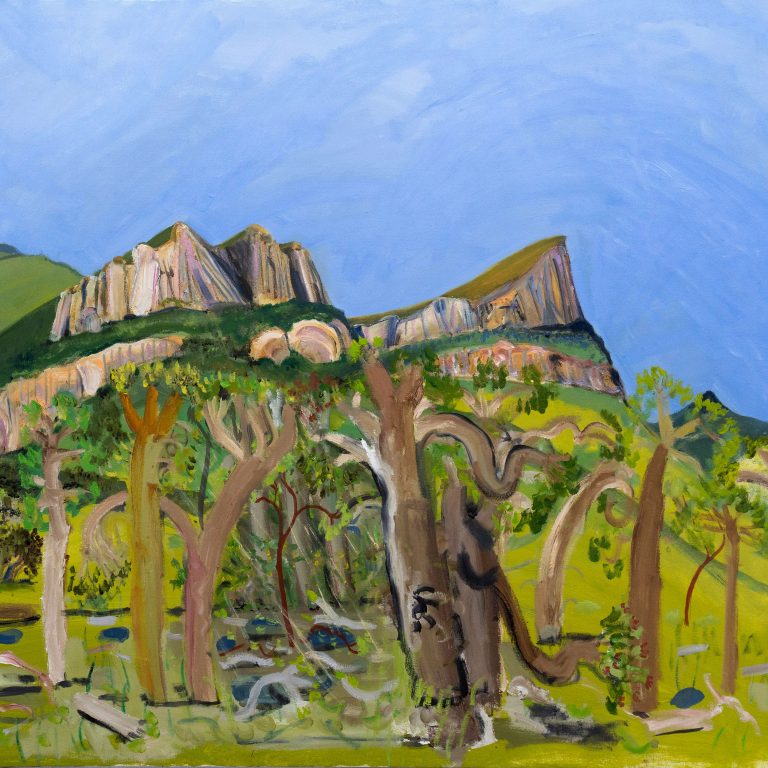

Asher’s art, I love it all; its creation tells a story of his strength and determination, it is his very true legacy. Asher is able to produce large walk-through pictures that make you feel glad to be alive. He studies the universe in a unique way, and observes the detail in small, tiny things: minuscule signs of life and the remnants of nature’s footsteps, hidden little gems. His art is magical and always beautiful. It connects with humanity and it does much more than we often ever care to admit. Here I will attempt to shed some light.

It’s difficult to fathom the scale of Asher’s work. However one of my most precious recent memories is of his 2013 Cosmotifs retrospective exhibition that went a long way to explain this. The exhibition staged at the Benalla Art Gallery in regional Victoria, was centred around a massive visual landscape of unusual wonder and complexity. The work in the room seemed to engulf its viewers. More than that, more kindly, it held and caressed the soul. It felt like walking into a deep hidden cave decorated with unfolding delights of stalagmites and stalactites, with a wealth of colour, depth and shape to lose yourself in and and to marvel at.

Featured paintings like About Time, 1990 (resin, pigments, cane and and paper offcuts on board), is almost 4 metres high. Like many of Asher’s pieces it is loudly three-dimensional, possessed of a width and depth that draws the eye in, sending it travelling in spirals, traversing its black, white and coloured cane and resin paint segments with desire. This action is absolutely addictive viewing; it is like peering over the top of a gigantic maze that deconstructs the mind and frees one’s thoughts. At a distance it appears almost completely black and white, partly confused. As you step closer and closer, the 3D transmodifying imagery pops out, and its twinkling coloured confetti of gemstone like pieces announce themselves, becoming a wonderous sight, elevating the experience.

Introspection, 2011 (enamel paint, mirror on board – seen the background of this article’s opening image) is a challenging work. Within Cosmotifs, it was a powerful focus – hovering over the room and connecting with every other piece on display; reflecting in the inky darkness of its central, deep black circular mirror many unexpected shapes and architectural aspects and views of both the room and the other paintings. This ‘Big Brother’ focal point appears like a dark menacing eye, polished to a silken perfection, waiting and watching, peering both at the universe and down upon its viewers, fear-inspiring, completely horrifying. The mirror presents itself as a black hole, threatening to absorb and compress the room into one central gravitational pinpoint, a singularity of inconceivable mass.

Asher’s son Luke admits he sees something dark and sinister in the work Vis Viva, 2011, enamel on board, which appears to me as a wall of of glistening hanging icicles backlit with a colourfully life-giving tropical forest landscape beyond. Perhaps this wall of ice, or shapes of whatever they may be, as Asher says, appear ‘man-made’, not of the natural world, and therefore they conflict with our own securities, our safety net. Asher says he was not surprised that Luke was almost afraid of the painting. I see a place beyond the ice wall, a landscape that we so desperately want to reach out to, to touch. Asher holds us back, forcing us to fall in love with the ice.

Multiverse, 2010, painted plywood, is perhaps my favourite work. It comprises eight 1.5m x 3m panels that hang together as a room-long seamless stitching of layered circular shapes, all positioned and painted with exacting critical detail and beauty. Multiverse and its 3D components seem to float and move as the eye studies it. It moves, ebbing and flowing like oceans of ripples and waves, peaks and troughs that comfort the viewer with a new visual representation of infinity. Infinity as a concept, a universal reality, now becomes something to be loved and embraced, no longer incomprehensible. In our deepest night’s sky there is delight and wonder as we gaze out into the cosmos, looking through our Milky Way. Man’s spirit compels him to bravely venture forth and beyond, just as our forebears travelled Earth’s vast oceans in search of the unknown – driven to conquer and make new discoveries. With Asher’s teaching, his profound and powerful sentiments, we can finally learn to simply be – to experience, to explore, to feel the true meaning of life and love, and that is to accept and connect. Asher makes us do this, and it is a beautiful feeling.

I remember the 2013 exhibition in Benalla as an important moment in Australian art history, finally affirming Asher Bilu as a mind, a creator, of the highest calibre, as good as Australia and perhaps the world ever will see. I am not surprised it has taken Asher more than two thirds of a lifetime to be discovered and celebrated. His genius is far ahead of what any average gallery curator could possibly begin to comprehend: there is no pigeonholing, no easy descriptor, no category, if you prefer. If anything Asher Bilu is a category in himself, demanding recognition.

Asher is a beautiful man. I know that he moves through life with an appreciation of all around him and of every life. Often, he talks of the little joys, the happy faces on his grandchildren, and how they too discover new visions of light and expression in their youthful worlds. Asher also never stops searching, admiring and discovering detail in his own world. I was fortunate enough to sit alone with him at the Benalla Art Gallery and witness the joy of expression on his face as he exploded in verse, pointing to the water fountain on Lake Benalla. ‘All of these tiny water droplets are moving to the east, then to the west, dancing in the wind, they are ballerinas,’ he said. ‘Isn’t life just so amazing, beautiful?’

This is the gift of an artist: to see what others cannot, to explore detail in the macro and in the miniature. Asher’s world of vision can extend past the greatest depths of our solar system and then fall quietly, internally, softly down to perhaps just one single grain of sand, sitting silently and perfectly, centred on a polished sheet of glass. The glass admires its one vital ingredient, and Asher admires how the winds of time have withered the sandstone down to this tiny speck. Cosmotifs, in many ways, is a journey into the unknown, but it is also a journey that takes us through a warm, comforting world.

One work that stays powerfully embedded in my mind is the major installation: M Theory, 2010-2011, acrylic on plywood, string (2,000 components). It continues to inspire me to ask one question of myself and of my world. That is, quite simply, ‘Why?’ At the moment it truely captivated me I notice that I was absolutely alone in the gallery, just before closing time, on a quiet, wintery Sunday afternoon, several weeks after a hugely attended celebratory exhibition opening. With all the energised and excited faces gone, all the spirit, love of connecting with people, had eroded me. I was there alone with the work, sitting on the floor with it right next to it. I remember feeling more connected to it, I felt its vastness. I wanted to step right into it – this three-dimensional picture and lie inside its boundaries, like lying in summer’s long grass. But I just sit with it, as one might sit silently beside a well-respected friend.

I imagine that one day the people of the future, with their digital archeology, will rediscover this work, and the accompanying photographic images of it. I hope that, as Asher Bilu did, they will painstakingly piece it back together for all to admire. Truly great art commands respect and is not forgotten. It is one of man’s great inventions. Looking at M Theory I am happy. There can be no better feeling. Asher, I thank you.

Comments are closed.